The teaching profession in Britain, where I currently reside, has very largely heard the sociolinguistic music: The facts of linguistic diversity and language change are generally accepted, teachers acknowledge most of the elementary facts about language, and dialect differences are not viewed in the same light as hideously disfiguring skin diseases. I had begun to think there was little danger of the British teaching profession being disrupted by an outburst of race or class bias masquerading as dialect purism comparable to the awful Oakland “Ebonics” brouhaha of 1996 (see my “Language That Dare Not Speak Its Name,” Nature 386, 27 March 1997, 321-322).

But recently the Colley Lane Primary School in Halesowen, in the West Midlands, sapped some of my confidence with a campaign to humiliate its own students by denigrating their native mode of speech. The school issued a list of 10 phrases that are to be banned from school premises, banned simply because teachers think they represent features of the local dialect.

The dialect in question is that of the Black Country, a region of the West Midlands to the north and west of Birmingham. You’ll be relieved to learn that “Black” here has nothing to do with race. The area was for a long time a center of coal mining and industrial activity, and the associated griminess gave rise to the sobriquet.

Here is the list of putative local dialect features that the Colley Lane teachers have banned from their elementary school:

- “They was” instead of “they were.”

- “I cor do that” instead of “I can’t do that.”

- “Ya” instead of “you.”

- “Gonna” instead of “going to.”

- “Woz” instead of “was.”

- “I day” instead of “I didn’t.”

- “I ain’t” instead of “I haven’t.”

- “Somefink” instead of “something.”

- “It wor me” instead of “it wasn’t me.”

- “Ay?” instead of “pardon?”

The ignorance of English dialects displayed here is shocking. The majority of the list covers features that are not local to the Black Country at all.

Was for were in the paradigm of be occurs in many nonstandard dialects of English, in America as well as Britain, and ain’t occurs in all of them.

The reduced-stress form of you that novelists write as ya (International Phonetic Alphabet [jə]) is not even nonstandard, only informal: In a sentence like You can’t refuse a request like that, even if you want to, virtually nobody pronounces the occurrences of you as [ju:].

Gonna ([ɡənə]), as a verb of near-future temporal aspect, is likewise found in most varieties of Standard English: Very few speakers say [ɡoʊiŋ] in the sentence that is formally written I’m going to do it.

“Woz” seems to be just a pointless deliberate misspelling of a normal British pronounciation of was ([wɒz]).

“Somefink” for something is a nonstandard pronunciation, but is just as familiar from other dialects such as Cockney as from the Black Country: Labiodentals like [f] are substituted for interdentals like [θ], and voiceless stops are inserted adjacent to nasals.

And finally, “ay” seems to be just the usual request for repetition or confirmation that is spelled “eh” in representations of Canadian English and pronounced [ei].

So nearly all of the items on the list are simply familiar features of nonstandard dialects spoken around the world, some of them present also in informal Standard English (the way the teachers doubtless speak it).

What we are left with is the trivial matter of three pronunciations of negated auxiliary verbs: In the Black Country, apparently, we find cor for can’t, wor for wasn’t, and day for didn’t.

So what’s the appropriate reaction to such small but clearly nonstandard local dialect features? Should they be banned on school premises?

Linguists have been here before. It was established in the 1960s, through painstaking applied sociolinguistic research in Scandinavia as well as the United States, that there is a clear outcome difference between two strategies relating to local dialect speech: (A) strictly banning the local dialect and insisting on the prestige standard in class from the outset, and (B) accepting and welcoming local dialect speech at first and then gradually transitioning students toward the standard language over a year or two. The bottom line is that B was found to work better than A. Children improve more, in all subjects, under policy B. (Notice, I’m not advocating that we should pretend nonstandard features are standard; I’m talking about what empirical research shows is the most successful way of inculcating the standard.)

Fifty years later, the Colley Lane Primary School in the English Midlands shows us that educated people are often pretty clueless about dialects of their native language, and that it takes a little while for academic research on educational matters to have any real effect. In fact, when it comes to language, the time taken for research to change classroom culture and practices might be better measured in decades or centuries than in years.

Quickly, now, without checking any dictionaries or usage guides: which of the following expressions is original, standard usage?

Quickly, now, without checking any dictionaries or usage guides: which of the following expressions is original, standard usage?

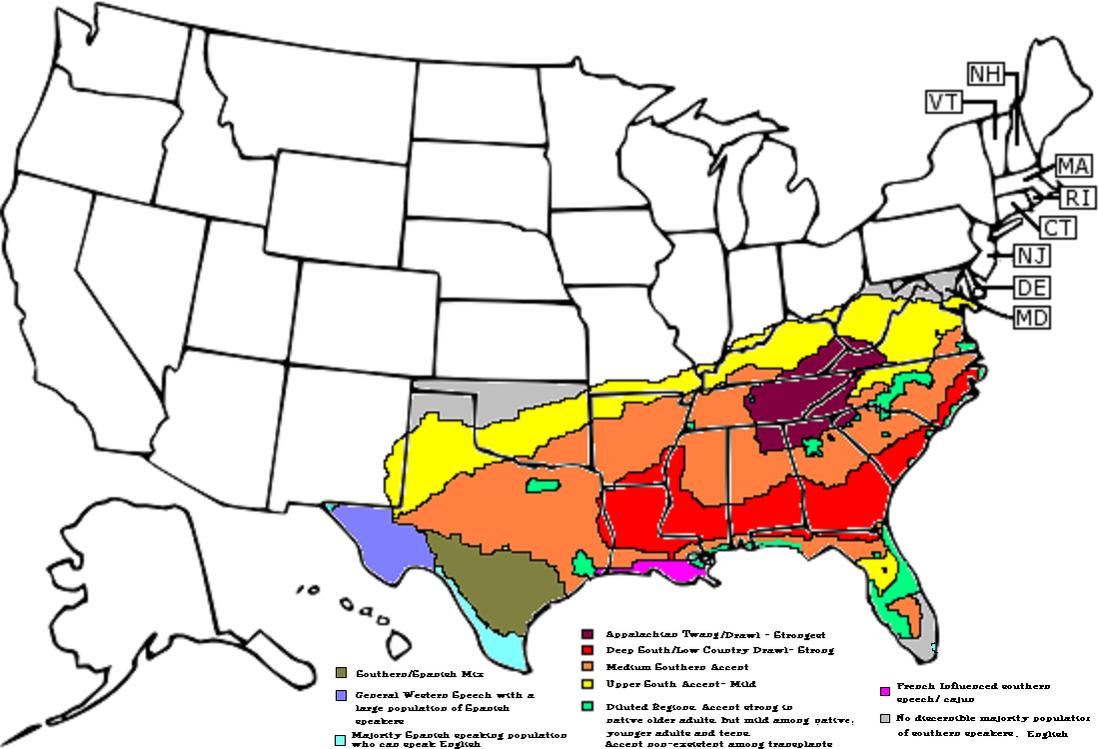

If you want to know how Americans speak, the go-to source is the quarterly journal

If you want to know how Americans speak, the go-to source is the quarterly journal

![202750507_448f2d6ca0[1] (2)](http://chronicle.com/blogs/linguafranca/files/2013/11/202750507_448f2d6ca01-2-300x210.jpg)